In the past year, many authorities have declared the Maryland darter fish (Etheostoma sellare) extinct. This fish was the only animal known to occur solely in the state of Maryland and nowhere else in the world, and also has the dubious distinction of being the only United States freshwater fish to go extinct in the nation’s recorded history. The story of the Maryland darter can teach us some of conservation’s most valuable (and often counterintuitive) lessons.

Astute readers will note that we said that “many authorities have declared” the Maryland darter to be extinct. The first question on many people’s minds will be, “Well, is it extinct or isn’t it?” This seems like it should be a simple question to answer – extinction is, after all, a definitive state of being (or non-being). Tyrannosaurus rex is extinct. Gray squirrels are not extinct. Establishing the actual proof of extinction, though, is anything but simple. Proving an animal still exists only requires one specimen. Proving an animal no longer exists runs into the old aphorism “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” How can we be sure there isn’t a Maryland darter still swimming out there somewhere? We can’t, and this uncertainty is what spawns popular frenzies over so-called “Lazarus species” – species thought to be extinct only to be rediscovered many years later. The alleged rediscovery of the ivory-billed woodpecker in the mid-2000’s, still unproven, is a prime example.

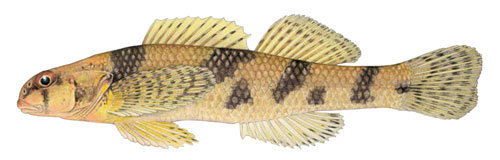

So, what do we know about the Maryland darter? Unfortunately, not very much. This species wasn’t even described by scientists until 1913, and at that time, it seems it was already very rare and restricted to just a single river system in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. A bottom-dwelling fish that fed mainly on aquatic invertebrates and reached a maximum size of about three inches, the Maryland darter’s striking color pattern and unusual body shape and habits made it the subject of much curiosity among fish researchers. No one managed to catch another darter for almost 50 years, but the species was “rediscovered” on 1962. More than one hundred specimens were collected during the following twenty or so years, but always singly or in small groups and always from just a few creeks flowing into the Susquehanna River. The last Maryland darter sighting was in 1988; none have been seen or caught since. No one has ever observed the fish courting or laying eggs; its reproductive needs and habits were always a mystery.

Well, the darters disappeared for 50 years once, so who’s to say that a mere 34 year absence is enough to call them extinct? Well, for one thing, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources has been undertaking intensive surveys for this species since 2008, seining, electroshocking, trapping, and trawling both creeks where darters have historically been found. So far, they’ve come up with nothing at all, even in areas where dozens of darters were collected between 1962 and 1988. On top of that, real demonstrable changes to the local watercourses due to agricultural runoff and the construction of the Conowingo Dam make it plausible that the darters could have been driven to extinction.

The Maryland darter was a great example of a species that, unfortunately, seemed destined for extinction. It had an extremely limited distribution, occurred in low numbers within that distribution, and the causes of its decline were suspected but never proven. Preventing this extinction, even with the most stringent protections from the Endangered Species Act, would be a very tall order. This is all the more reason for us to study and protect our native wildlife before they become so rare that we can only watch as they disappear from before our eyes.