Walking around the woods in northeastern Massachusetts on the last couple of warm days it feels to me like a biological time bomb is due to go off in the very near future. The wetlands near my home in Concord, MA are mostly quiet now, but under the leaf litter in forested areas throughout much of our area, frogs and salamanders are barely restraining themselves, waiting for a brief night-time rain to burst forth and migrate, en masse, to nearby vernal pools and wetlands to fully launch the Massachusetts spring.

I have a deeply ingrained sense of how dramatic an event the nocturnal spring-time migrations of wood frogs, spotted salamanders, blue-spotted salamanders, and spring peepers can be, having spent many years in the field studying these animals and often counting them as they migrate. In 1991, I was a Ph.D. student at Tufts with the bright idea to study the movements and ecology of spotted salamanders and wood frogs in the forests, where they live most of their lives. These beautiful and iconic amphibians gather in vernal pools in very early spring to mate and lay their eggs. They then disperse within days back into the forests whence they came to live out the rest of the year.

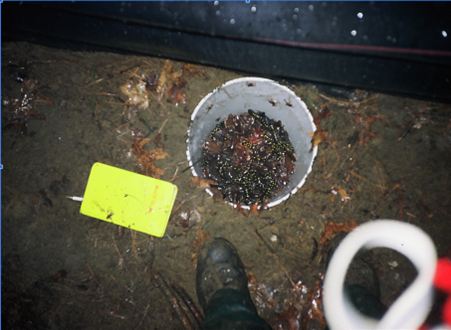

I wanted first to count the number of spring-breeding amphibians that migrated to and from a largish (0.5 acre) semi-permanent pond in Concord and to get a better sense of which areas of the forest they were coming from or going back to. So, with the help of a few die-hard friends and volunteers, I dug an 1,100 foot-long continuous 8” deep ditch around the shores of the pool, buried the bottom of 3-foot high plastic silt fencing in the ditch and staked up the fencing to make a barrier to frog and salamander movement into and out of the pond, and then dug 32 pairs of large holes tight against either side of the fence into which I inserted five-gallon buckets with drainage holes buried to their rims in the forest floor. I had created a “drift fence – pitfall trap system”; nearly every frog and salamander trying to get into our out of the enclosed pond would hit the fence, walk or hop along it, and then fall obligingly into the buried buckets, from which my assistants and I could extract them, mark and count them, and release them to continue their voyages on the other side of the fence.

We knew in March 1991 that the conditions, as they are today in late March 2023, were primed for the amphibian migration. The soil had long ago thawed from winter’s chill, snow cover was gone, and the days were fairly warm. I also knew that rain was forecast for the night of March 17, St. Patrick’s Day. We worked very long days and finally finished the last bits of fencing and buried the last buckets on March 15. Before the rain began on the evening of the 17th, about 6 of us gathered to await the oncoming amphibian storm. I knew a fair bit about these animals and had worked with them for a few years, but I had no real idea of what we were in store for that night, nor the scale of this particular amphibian migration event.

Our group spent the entire night, going well past dawn on the 18th, very slowly circling around the drift fence, counting,measuring, marking, and releasing frogs and salamanders. Though I don’t have the exact numbers findable at this moment, I recall them pretty well. By the time my field crew and I staggered home in the morning, we had counted and released more than 3,500 wood frogs, well over 1,000 spotted salamanders and a couple of dozen blue spotted salamanders, 1,500 spring peepers, and several hundred red-backed salamanders and green frogs. One bucket alone, seared in my memory, was literally half filled with a writhing mass of hundreds of frogs and salamanders. A friend of mine who is one of the most accomplished naturalists in Massachusetts was reported to have left our group around 4 in the morning muttering that once you’ve seen your first 1,000 wood frogs, you’ve seen them all.

The migrations of wood frogs, spotted salamanders,and several other amphibian species from forest to vernal pool and back to the forest again in early spring is one of the transcendent wildlife spectacles of New England and such migrations happen, at scale, at hundreds of locations in Massachusetts. Sadly, because the frogs and salamanders almost always migrate at night and in the rain, relatively few people have witnessed this phenomenon. These massive breeding migrations, followed some months later by the movement of newly metamorphosed juvenile frogs and salamanders from the often drying vernal pools back into the woods and to wetland areas that may be several hundred yards away have tremendous and poorly studied ecological implications for the health of our forests. On the forest floor, the salamanders and frogs are often the most important predators of insects and other arthropods that shred the leaves that drop each autumn. Their migrations link the forest and wetlands energetically, moving nutrients back uphill from the vernal pools, which can be as thick as porridge with living animals and algae, into the surrounding woodlands. This greatly enriches the soil. Those nutrients contribute to the growth of the trees that capture carbon and produce leaves that fall and in turn are decomposed and help fuel the food web of the vernal pools the following spring.

So, grab a light, rubber boots, and some rain gear, and head out into the woods – ideally with someone who can point you in a promising direction – on any rainy night for the next few weeks. Listen for the quacking calls of wood frogs and clear tinkling, deafening in proximity, of spring peepers, and enjoy a spectacular wildlife migration that may be happening right now in the woods near your home.