Zoo New England’s second new international partnership is with BirdsCaribbean, a nonprofit with a long history of promoting the study, protection, and appreciation of birds in the Caribbean islands. The islands themselves are not terribly large, but they are home to incredible biodiversity. The Caribbean plays host to more than 700 different bird species every year (more than twice what we see here in New England) and of those, more than 100 species are endemic to a single island and found nowhere else in the world. These rare treasures could disappear forever if they are not protected.

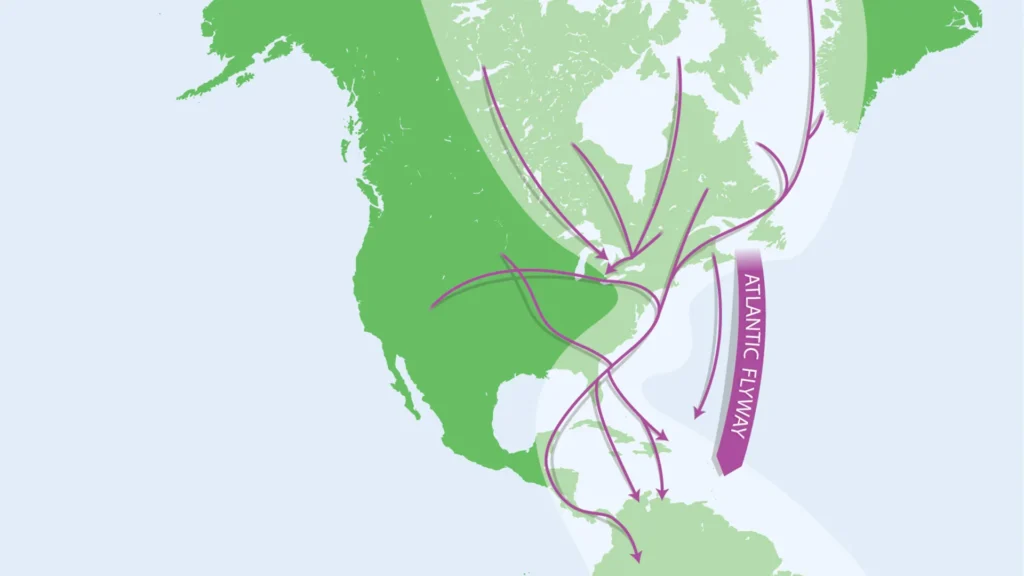

The endemic birds are incredible, but another crucial feature of the Caribbean is its importance to migratory birds. The Caribbean lies on the Atlantic Flyway, which is like a superhighway for birds that spend the summer in North America but need to fly farther south for the winter. A combination of favorable winds, good rest stops, and terrain like the Appalachian mountains that provide natural updrafts funnel millions of birds every year along the exact same migratory routes.

Migration is a difficult, dangerous, and exhausting time for birds – they must leave the territories they know so well to fly across hundreds or thousands of miles of unknown territory, all on the fat reserves they have managed to put on after the breeding season. Good rest stops with safe places to sleep, plenty of food, and clean water are essential for birds, and the Caribbean islands are such oases amidst the inhospitable salt water of the Atlantic ocean.

Birds migrating through the Caribbean are hoping to find food, shelter, and safety, but they face many threats. Development that destroys critical forests and wetlands deprives the birds of the food they need to safely complete their journeys. Hunting for feathers, meat, and the caged bird trade denies them the opportunity to rest safely and regain their strength. Scientists and concerned residents are doing their best to study and protect the birds, which oftentimes involves banding them. “Banding” (or “ringing” in other parts of the world) involves putting a small, lightweight metal bracelet with a unique ID number on wild birds.

If the birds are caught again somewhere else, the bracelet identifies the individual and tells us something about how and where birds move, their survival from year to year, and more. However, this only works if there is some central database or authority that keeps track of all the banded birds and their unique numbers, so that anyone who finds a banded bird can report it. In the USA, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) administers the federal bird banding program. The Caribbean, however, includes thirteen independent countries and has no such central organizer.

BirdsCaribbean aims to change that. Their Landbird Monitoring Program is training Caribbean residents to set up and maintain their own bird banding and monitoring schemes, and assisting them in creating a central data repository for all that bird information. As always with BirdsCaribbean programs, the central focus is on building confidence and capacity among Caribbean residents to take action for conservation in their own communities.

BirdsCaribbean is also funding the construction of new towers for the MOTUS bird monitoring network – a special series of detectors that can record the passage of migrating birds who are carrying a certain transmitter tag. Zoo New England has already funded one MOTUS tower here in Massachusetts, and supporting BirdsCaribbean’s Landbird Monitoring Program is a perfect way to connect the birds’ summer habitat here in Massachusetts with their migration stopovers and wintering grounds in the Caribbean.