Like all animals, food availability is crucial to the quality of Blanding’s turtle habitat. Particularly for our head started juveniles, a fast growth rate and large shell size is key to avoiding predation. We noticed that some of our sites had consistently faster growing turtles than others and set out to determine if the availability of certain prey items was the culprit.

For two weeks in May, we radio tracked 51 different turtles between Lowell Dracut Tyngsborough State Forest and Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge. Those turtles were then held in sterile tubs filled with warm water overnight. The next day, the water from those tubs were used to create water samples, while the solid matter was filtered out and collected for fecal samples. The turtles were then taken back to the location in which they were found via radio tracking and released .

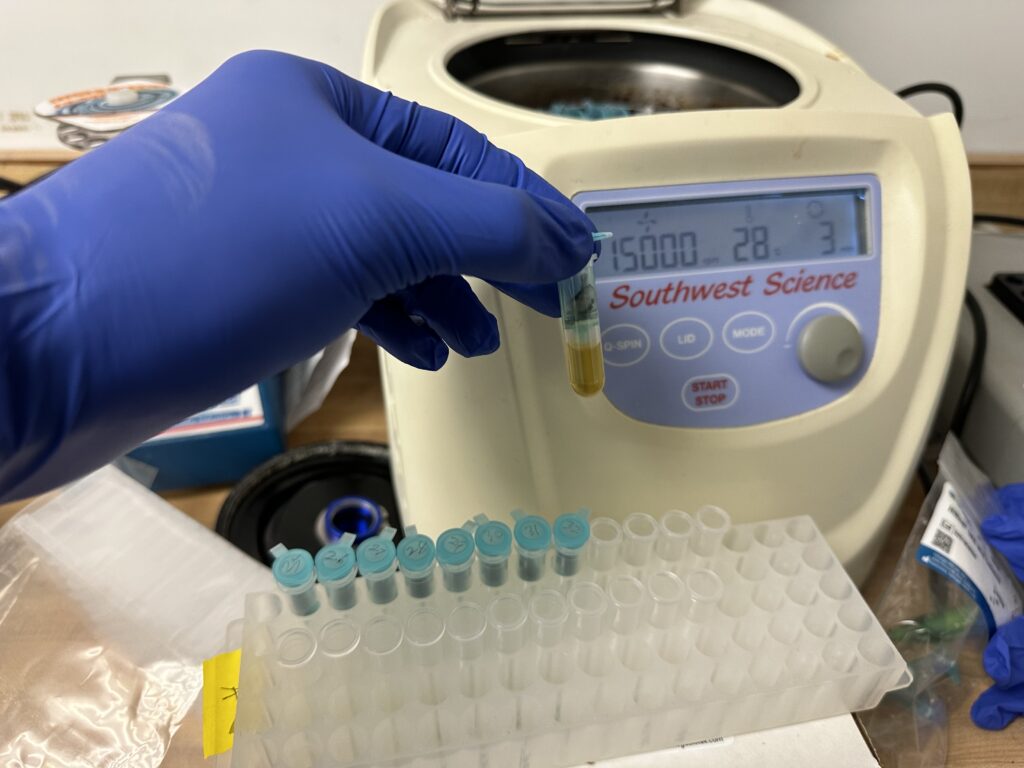

Last month we extracted DNA from those samples at UMass Amherst’s Elkinton Lab. Traditionally, in turtle diet studies, researchers screen the fecal samples and identify the species from pieces of exoskeleton, skeleton, or other hard remnants. Now with DNA meta barcoding technology, in our study we’ll be able to identify soft bodied prey like leeches, worms, and even amphibian eggs.

Preparing DNA for interpretation involves filtering out and extracting it from samples before, then amplifying it with standard PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) techniques to produce millions of copies of DNA segments ready to be analyzed. With the filtering and extraction steps completed for our first round of samples, we are preparing for our second round of fecal sample collections, which will then undergo the same filter, extraction, and PCR process and be sent out with our first round samples for sequencing.

We are just wrapping up our second round of this collection process to take into account the different seasonal prey availability. One of our most notable observations during this study occurred during this second round on only the third day in, when we came in to begin processing fecal samples to find an impressively substantial sized snake skin floating in the water with an adult female turtle.

Our goal was to track and collect as close to the same set of turtles as the first round as possible, to allow for a greater direct comparison across individuals and location. Of the original 51 turtles we collected for the first round, we were able to collect 45 of those same turtles for this second round, which included many difficult turtles. Several of our biologist took a swim in deep channels and were stung by bees to access these same turtles. The remaining turtles were either unobtainable due to circumstances such as a turtle losing their radio, as seen in the photo to the right, or enjoying a spot completely out of reach.

Looking forward, we hope the information that we gain will help us find sites that our head-started turtles will do well in and provide some solid insights into what this species prefers to feed on.