I have to start this story a ways back – roughly 50 million years ago, when the land mass we now call India experienced the equivalent of an extremely slow-motion car crash into the continent of Asia. That crash – which is still going on today, at an estimated two inches of upward motion a year – crumpled Asia’s bumper so substantially it created the greatest mountain range on earth, the Himalayas. This includes the tallest mountain in the world, Everest, and contain over 100 mountains that reach at least 23,000 feet in elevation (for comparison, the tallest mountain in North America, Denali or Mt. McKinley, is just over 20,000 feet tall).

With such extremes, and so much time, it’s no surprise that the Himalayas have evolved a host of amazing mountain species that are endemic – found nowhere else on earth. This includes a spectacular group of species, ones that the eminent conservationist George Schaller dubbed the “mountain monarchs:” the wild sheep and goats of the Himalayas.

Perhaps the most spectacular of these mountain monarchs is the markhor. This wild goat, the largest on earth (although the stocky Siberian ibex can be heavier) lives on the steepest, most rugged terrain on the planet. Here the markhor’s rubbery hooves enable it to climb the most precipitous cliffs, walls of rock that seem to have no possible way up. They can even climb into the canopy of oak trees to munch on the leaves – not bad for an animal with no fingers or toes and that can weigh over 200 pounds!

Male markhor are spectacular to look at, too. They have enormous, cork-screw horns that can stretch five feet in length, as well as great beards of hair that cover much of their chest and almost reach the ground.

Let’s step back in time again. When India crashed into Asia, it appears to have trapped in between them what some argue was its own, geographically distinct island, now called the Kohistan Plate. This area is the meeting-place of three of the greatest mountain ranges on earth – the Himalayas in the strictest sense, along with the Karakorams and the Hindu Kush (which are considered sub-units of the greater Himalayan range).

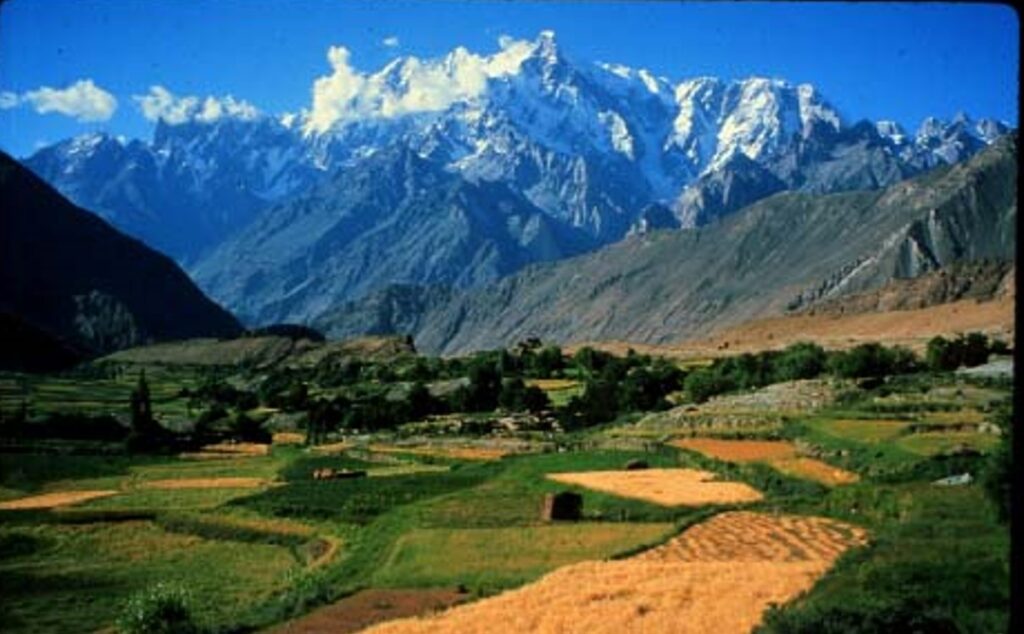

This spot, located in northern Pakistan, is steep, rugged, and isolated, with the mighty Indus River roaring like liquid concrete through a barren, desolate valley at 4,000 feet, and with Nanga Parbat, the world’s ninth highest mountain, rising almost directly above, to about 26,000 feet. In this fierce and rugged land live a similarly fierce and rugged people. Separated by the mountains from the rest of Pakistan, they were often at war with each other (most valleys considered themselves their own tiny kingdoms) but never lost to outsiders, including the English and the Pakistan government itself. Because of that they are Tribal people, owners of their land and all that lives there. Including the markhor.

Markhor have long been treasured as icons in this region, and in fact are the National Animal of Pakistan. Historically few people hunted on this isolated, poverty-stricken land. Often there were only one or two ‘shikaris’ or hunters in any valley who might own an old, front-loading blunderbuss and would on occasion shoot a markhor, to great local acclaim.

However, as the world modernized and conflict repeatedly broke out in the region, modern weapons became available, and often cheaply. Soon, every young shepherd had an accurate rifle or machine gun on his back – and if you’ve ever given a squirt gun to a young man, you know you can expect to get wet.

Not surprisingly, soon markhor became rare in these mountains, as did much of the other wildlife in the region (Schaller, who coined the term “mountain monarchs,” wrote an entire book about the region in the 1970s depressingly titled “Stones of Silence”). Eventually markhor were listed as Endangered, and given the even more drastic status of Critically Endangered in Pakistan. The population was rapidly decreasing from overhunting and likely would soon disappear altogether.

Before that happened, however, the local communities stepped in. Recognizing that the markhor was disappearing, they outlawed hunting. In these tight-knit communities, people follow the rules, and outsiders don’t usually enter other people’s lands to poach, as that can lead to violent reprisals and even long-standing blood feuds.

With volunteer community rangers patrolling the mountains, keeping an eye out for any scofflaws while also tracking and counting markhor, these iconic wild goats began to come back. Within two decades the population went from rapidly decreasing to increasing, to roughly doubling in numbers. The successful community led efforts here, and in a few other locations, led to the markhor being globally double-downlisted in status by IUCN (the global authority on species’ status), from Endangered past Vulnerable to Near-Threatened.

Today is May 24, and this date has just been declared International Markhor Day by the United Nations. So let’s all give a cheer to an incredible conservation success story – the recovery of the markhor – and to the people who made it happen.

Zoo New England supported this successful field program for a number of years, providing funds for supplies and equipment for ranger patrolling and markhor surveys. If you want to see the mighty markhor in person – along with the amazing, ghost-like snow leopard that is its main predator in the wild – come visit Stone Zoo’s Himalayan Highlands!